Principles of Separation and Sustainable Safety

NB - this post is a DRAFT and does not yet represent Embassy policy. If you've any comments they can be added here or discussed more fully on the forum (login required).

This was the first breakout session on the Infrastructure stream of the Embassy Policy Bash.

Principles of Separation and Sustainable Safety

We started by realising we had to define our terms:

Hierarchy of Provision

For a long time, UK cycle policy has been arranged around the 'Hierarchy of Provision' which provides a list of options to 'consider' in order:

Traffic reduction

Speed reduction

Junction treatment, hazard site treatment, traffic management

Reallocation of carriageway space (e.g. bus lanes, widened nearside lanes, cycle lanes)

Cycle tracks away from roads

Conversion of footways/footpaths to shared use cycle tracks for pedestrians and cyclists

There are a number of things wrong with this.

First, there's no real enforcement implied by the word 'consider', so there's no confidence that the higher priority actions will ever get implemented if they're at all politically difficult.

Second, there are no numbers against the first two: what speed should traffic be reduced to? What volume of traffic is acceptable?

Third, options 4 and 5 are somewhat unclear: does reallocation of carriageway space include separated cycle tracks or just paint on the road? Are 'cycle tracks away from roads' things like green ways or paths through parks only or do they imply parallel segregated paths?

Principles of Separation:

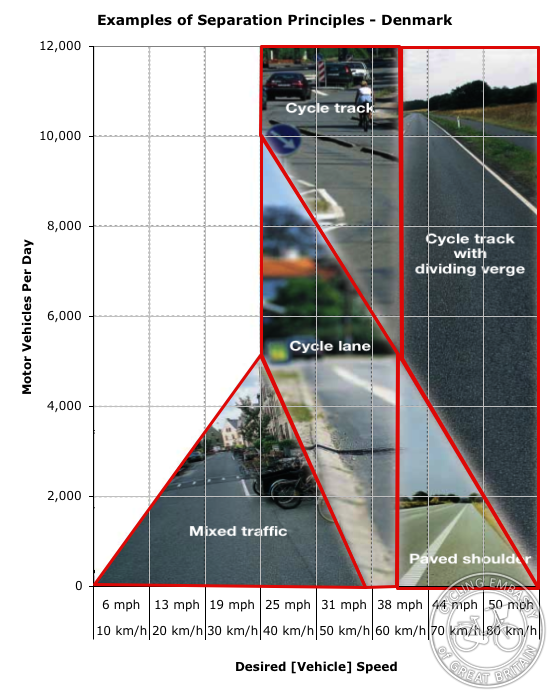

In contrast, the Danish 'principles of separation' attempt to classify the sort of cycling facilities that should be put in based on the speed and density of traffic. This is a good start, and much more prescriptive than the hierarchy of Provision guidelines (image taken from Planning of Traffic Areas via http://karlmccracken.sweat365.com/). However it does leave us open to getting potentially narrow and subjectively unsafe cycle lanes even on quite fast and busy roads. This led us on to:

In contrast, the Danish 'principles of separation' attempt to classify the sort of cycling facilities that should be put in based on the speed and density of traffic. This is a good start, and much more prescriptive than the hierarchy of Provision guidelines (image taken from Planning of Traffic Areas via http://karlmccracken.sweat365.com/). However it does leave us open to getting potentially narrow and subjectively unsafe cycle lanes even on quite fast and busy roads. This led us on to:

Tracks vs. Lanes vs. Paths

Discussions about cycle policy often get confused because some people use the terms 'cycle paths' and 'cycle tracks' and 'cycle lanes' interchangeably. For the purposes of discussion we define them as follows:

'cycle lanes' are on-road lanes for bikes delineated solely by paint and generally not separated from traffic except by the width of a line of paint (although some US cities put in 'buffered' bike lanes where hatching is used to create a buffer zone between the cyclist and either passing cars or opening car doors).

'cycle tracks' are separated cycle facilities which are generally divided from the rest of the road by a kerb or verge of some sort, and are also ideally at a different level from the carriageway and from the pavement, making them more obvious to the visually impaired. They do not include shared pavements

'cycle paths' are ambiguous and as nobody in the room could agree what they meant we decided to avoid using the term.

We also agreed that, in general, we felt that, where possible, cycle tracks should be used wherever separation of bikes from other traffic is needed. Cycle lanes on their own don't do much to give cyclists a feeling of safety although they can be useful where there is no space for full tracks on short stretches of road, in order to provide a joined-up route.

Sustainable Safety

The Dutch don't have anything as simple and prescriptive as the Danish principles of separation. Instead they work from the basis of 'sustainable safety' which has five main principles:

- Functionality of roads, based on 3 main road types: main roads (large roads, like trunk roads in the UK), access roads (small roads, such as residential streets) and distributor roads (somewhere in the middle)

- Homogeneity of mass, speed, and direction, with vehicles with large differences physically separated from each other - vulnerable road users are incompatible with cars and lorries are incompatible with other vehicles; where physical separation isn't possible then speed must be reduced.

- Recognizability of the road design and predictability of the road course and road user behaviour so that road users automatically know from the design of the road what is expected of them

- Forgivingness of the environment (physical) and between road users (social),

- State awareness by the road user.

Taken from: http://www.swov.nl/uk/research/kennisbank/inhoud/05_duurzaam/the_five_su...

In order to directly apply the CROW manual guidelines, we'd first have to classify UK roads into the three main types (main, distributor and access). Unfortunately, such distinctions are much less clear cut in the UK with quite important trunk roads often running right through smaller towns and villages, and roads changing function from one intersection to the next (think of your typical busy main road through a town which might have parking, houses and shops on it yet also be laid out as a fast multi-lane road.

What are roads FOR?

We recognised that redesigning the entire UK road network was possibly a bit ambitious even for us, so we decided to take a slightly more fluid approach. We agreed that the most important question when deciding what sort of cycling facilities needed to go where: what is the road for? And what purpose does it serve within the wider network? Some roads will be important for bikes and not for cars (for instance a road on a popular bike route). Some roads will be important for cars and not for bikes (such as motorway access roads). Many roads will be important for both bikes and cars (the major 'desire lines' within a town or city) and shopping and residential streets are likely to be unimportant for both bikes and cars. Note that this is a simplification - a further dimension would need to be added for HGVs and also for buses. Where roads are important both for bikes and for other forms of traffic - so that radically slowing speed and/or cutting traffic volume is not an option - then those are the highest priority roads for putting in cycle tracks. This gives us not just a simple rule of thumb for deciding what degree of cycle infrastructure should go where, but should also provide a staged approach, allowing councils to prioritise roads where infrastructure should go first, depending on the purpose of the road.

We then took this basic principle and applied it to the next two infrastructure streams - thinking network, and redesigining a roundabout.